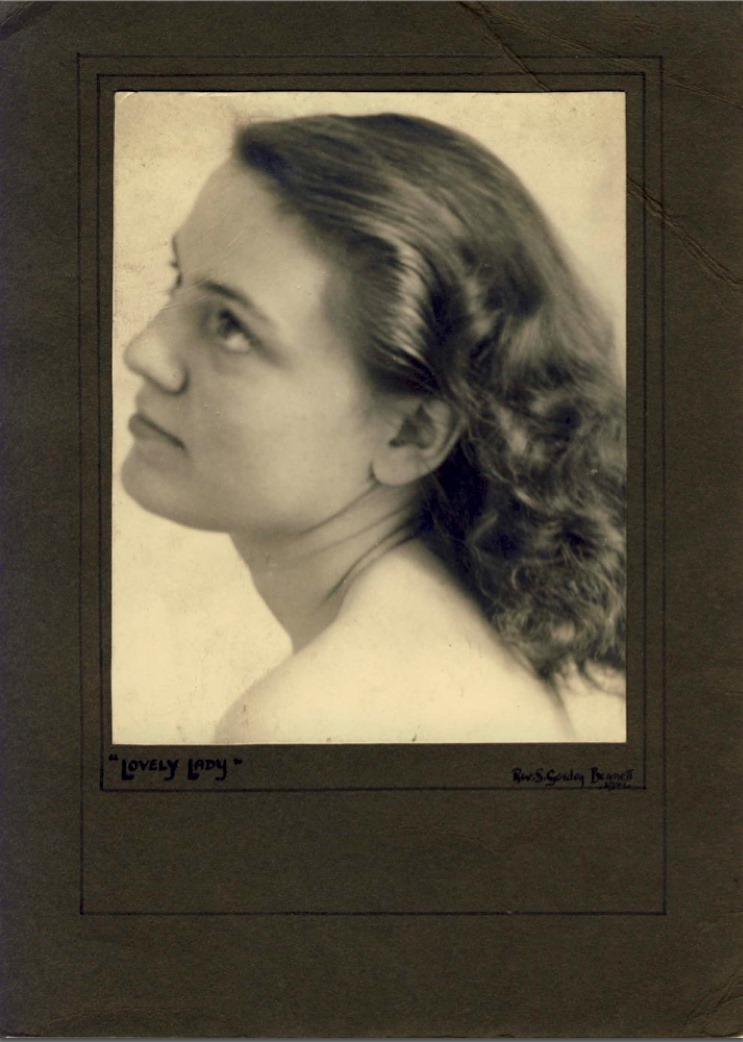

by Soprano, Christine Bennett

“I’m pretty confident that most people have a mixture of rôles – in that I’m no different: wife, mother, grandmother, graduate, retired Chartered Accountant, mildly sporty at school, lifelong singing enthusiast. I’ve also learned that supporting charitable causes brings me pleasure.

I’m old enough that I’ve had some experiences that might be useful to other people and the focus of this post is to draw attention to something that I had thought was frivolous and almost a waste of money but which turned out to be valuable beyond price… and that might just help someone else. It’s the story of how my father’s voice touched my mother long after she seemed so out of reach.

My father

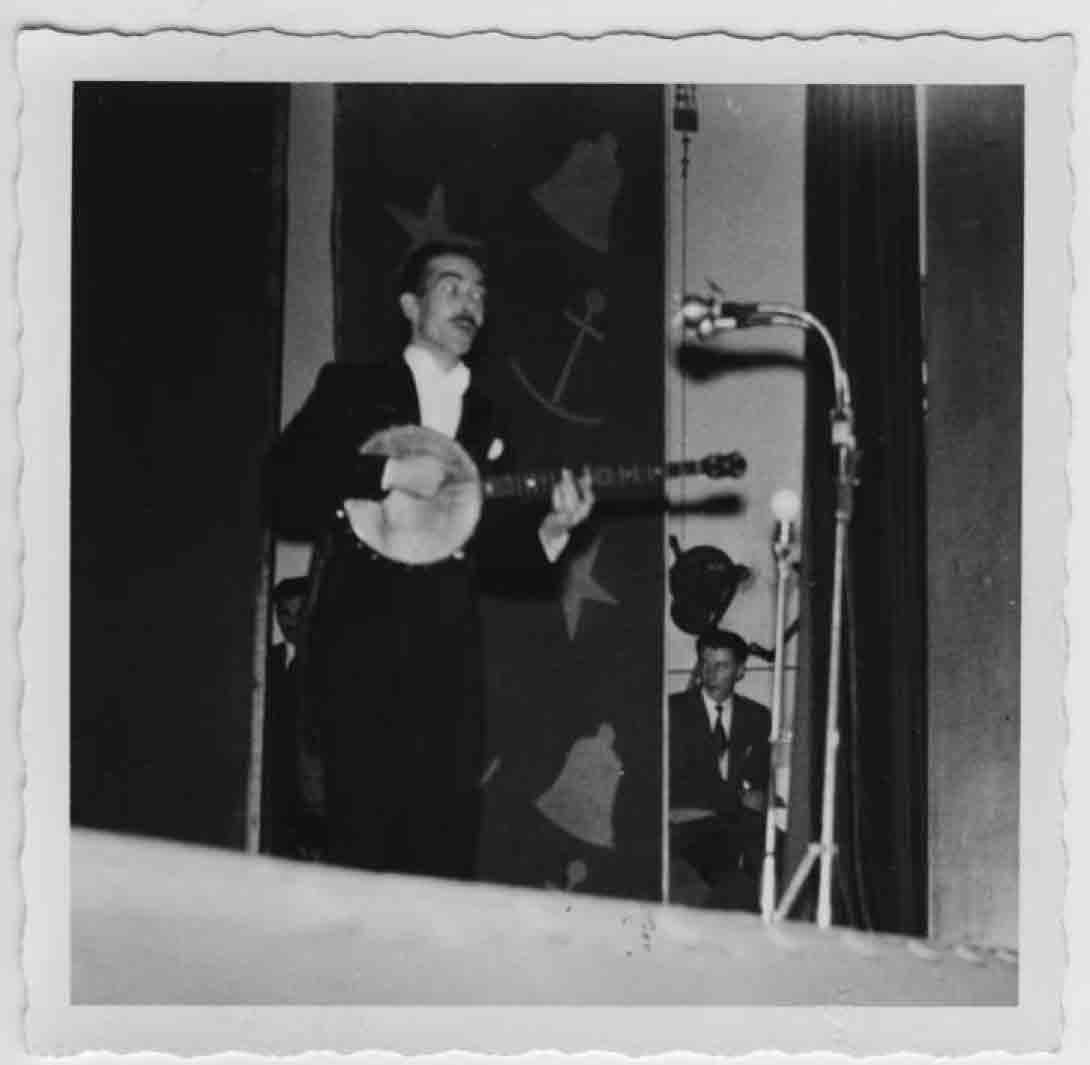

A Church of England clergyman, my father, Stanley Bennett, was good at a lot of things but the critical thing, in this context, is that he was a singer, with an ability to entertain – to “vamp” on the piano and play the banjolele formidably well. He loved music and was a versatile performer, being able to sing many genres in character. He shared that love of music with us all, and my own experience was of supportive encouragement to sing and to perform. He was a person who wrote his own songs and harmonised by ear, so that seemed normal to me, too.

He had kept scrapbooks of his life experiences, with newspaper cuttings, certificates, and photographs, and took advantage of new technologies that allowed him to record his performances and compositions on reel-to-reel tapes. And he made sure that he had a good quality microphone to do it.

The tapes included recordings taken from broadcasts by BFN (British Forces Network, subsequently BFBS), during our time in Germany. He had taken part in the Höhne Barracks “At Home”, where he was singing with a little jazz ensemble. There was also a recording of Stainer’s Crucifixion (as broadcast by BFN), in which he had sung the bass solos.

Another tape had recordings of him playing his own melodies on piano. Yet another had a recording of a “Gang Show” kind of entertainment that must have taken place in a local village hall. There were even some recordings of myself, as a child.

Losing my parents

My father died in 1980, aged only 64 – about 18 months before my parents would have celebrated their Ruby Wedding. After my father’s death, my mother went through different stages of grief – as we all did. The “black” days were frequent, at first, but gradually spread themselves out.

She (and we) were still subject to occasional “ambushes” of sight or sound or smell that would trigger a poignant memory, but we moved on with our lives. She organised her life so that she was within range of a town (for church and shopping) and still in touch with friends and her church. She organised herself some impressive holidays – including two trips to Ghana – and joined some of the family on their holidays.

With hindsight, we realise that there were some uncharacteristic behaviours creeping in: we really should have noticed when the mother, who’d been trained in the bank and looked after the family finances all her life, couldn’t remember whether or not she’d paid for something.

Eventually it became obvious that there was something more than just a bit of forgetfulness – she had been struggling with independence. Putting your mother into a home is not an easy decision, especially if she recognises that she can no longer choose to go out. My mother was in the care home for more than a decade.

Treasures

When we cleared out our mother’s house, there were lots of things to look after, in one way or another. She had organised us, some time before, by getting us to put labels on things that we might like to have, one day (circumstances unspecified). For whatever reason, my father’s old reel-to-reel tapes came to me. I knew that there were some interesting things there. During his time as an RAF Chaplain, he had recorded all kinds of interesting things – and I’d always been a bit of a “Daddy’s Girl”, so I rather fancied the idea of getting access to the recordings locked away in what was long past being “new” and was now almost “museum” media.

Once I’d got the idea in my head, I started to look around for a means of getting the tapes onto CD or into mp3 format. The tapes weren’t of broadcast quality, so radio tape-decks wouldn’t serve – they’d be spinning much too fast. I did some web-searching and found that a small business called Digital Copycat seemed to have good reviews and an attitude to care of the material that accorded with my own wish to cherish these unique tapes. I got in touch and drove one or two of my precious reels to their destination. Once I was notified that the process was done, I drove down with a couple more, and drove home with the results of the first expedition.

Harking back

When I played them, it was strange to hear my father’s voice again, after so many years, but lovely. By this time, my mother had long ceased to show any recognition of me, when I arrived to visit. We had tried playing CDs of “her” era’s pop music, or light classical music, but she had shown no discernible reaction. She had just continued to fidget or mutter and mumble.

I spent an embarrassingly large amount of money, recognising that you have to pay for someone’s time, if they’re going to look after your tapes and make sure that the final product is the right way round (not Side 2 before Side 1, for example).

Once I’d got a number of the tapes copied over, I started to put individual tracks onto my smartphone. I wanted to be able to play them for my mother to hear, so my husband nipped into a local department store and bought me a little speaker, so that the sound quality would be reasonable.

We drove the couple of hours to visit my mother and I went into her room, armed with my newly-uploaded recordings of my father. She was curled up as usual – muscular contraction had pulled her into something like the foetal position – and fidgeting and muttering and mumbling to herself.

I knew she didn’t react to things we played to her, so watched only in a spirit of “I told you she wouldn’t react”, as I set the recordings to play.

As soon as the sound was identifiably my father, she went still and quiet. She stayed still and quiet until all the recordings were played.

Letting go

About ten days after that visit, we had a late-evening phonecall from the care home, suggesting that she was “rather poorly” and we might want to come and visit. By that time I had a couple more tracks uploaded.

My brother, sister, and myself met up in my mother’s room and I played the tracks through a couple of times in the middle of the night. Some were upbeat, some were crooning love songs, some were church music. She hung on until the afternoon, and she slipped away to the sound of that precious voice that had meant so much to her.

Having defied the doctor’s prognosis two or three times before, I wonder whether that voice, when it reached her, somehow told her it would be OK to “let go”.

One of those tracks is the song “Just A Wearyin’ for You” which I recently performed online as a duet with my father’s recording.

Could it work for you?

Having seen how that particular voice seemed to have pierced the mists of dementia in a way that no other sound had done, I tell everyone I can that, if they have a recording of a special voice like that, it really is worth spending the money to get it copied into a format that will allow it to be heard again. It might not even be singing – it might be a speaking voice (a speech at a wedding or a party) – but it’s the specific timbre of a loved voice that may well reach the mind when other things do not.

This is really a very specific version of the effects of (e.g.) “Singing for the Brain” ™ that’s run by the Alzheimer’s Society. Music and singing really can penetrate in an effective and positive way to enhance the lives of those who are living with dementia.

Where to begin?

If any of what I have said has resonated with you, I encourage you to begin considering the possibilities and taking care with preservation. Have you got any old family films, videos, tapes, cassettes… ? If so, make sure that you keep them in conditions that mean that they won’t be damaged. If you can play them, safely, it’s worth making sure that they are correctly labelled. If you don’t already own the equipment, yourself, you should look around for reliable businesses to get them copied into more accessible media.

If you don’t have expertise yourself, it’s worth taking advice from someone whom you trust. If your tapes/cassettes/disks are unique, you won’t get another chance, if they are damaged in the transfer process (or lost in transit), so you will want to be very careful. I was too wary, even to send my tapes by post/courier: I took them myself.

Of course with all the technology at our disposal now, it would seem likely that recordings of your treasured voices may already exist in the palm of your hand, but do be sure and if not, make some. And we cannot assume out loved ones will know what to do, or be able to find your meaningful recordings, if you do not find a way to tell them what you might like to hear. Doing this sooner rather than later may be the wisest approach.”

Find out more

If you want to know more about living with dementia and its effects, the national charity the Alzheimer’s Society is an ideal starting point.

In Hertfordshire, there’s a local charity, Herts Musical Memories which is specifically picking up the former “Singing for the Brain” ™ sessions: www.hertsmusicalmemories.org.uk

If you knew my father, or would like to get to know him better, I made an online memorial to Stanley G. Bennett.

Share